Puerto Rico's Approach to Community Engagement

The Judicial Branch of Puerto Rico’s Office of Court Administration led the Puerto Rico team through its Office of Education and Community Relations (EduCo). Community engagement is one of EduCo's main goals. Their mission is "developing, applying, and managing education and community liaison programs to encourage a greater understanding by the community of its basic rights and responsibilities, as well as of the court system and how it works, and to foster community participation and integration with the Judicial Branch."1

Goals

- Explore opportunities to assist both youth and adults in addressing community conflicts.

- Gauge knowledge and attitudes towards the judiciary among youth and adults.

- Develop and strengthen ties between the judicial branch and youth as well as adult leaders.

Recruitment

The Puerto Rico team employed purposive and convenience sampling to recruit youth and adult community leaders to their community engagement sessions.

Engagement Structures

EduCo engaged both youth and adults in its engagements. Although there were common elements across the engagement sessions, there were also adjustments made to accommodate youth versus adult participants, and to accommodate the various relationships between EduCo and the specific groups.

EduCo had pre-existing relationships with the San Lorenzo and Alianza leaders, as well as with the Boys and Girls Club organization. One of the EduCo members also had prior interactions with the Crearte School.

Youth Groups and San Lorenzo

Breaking the engagement activities into two sessions for three of the four groups allowed EduCo to present back in Session 2 what they heard in Session 1.

Session 1:

- Cruise ship icebreaker

- World Café discussions

- Plenary discussion

Session 2:

- Team work icebreaker

- Summary of prior session

- Myths and Realities

- Follow-up planning

Alianza Leaders Group

Alianza is a less homogenous group of leaders representing communities from different municipalities of Puerto Rico. The president of Alianza requested a planning meeting to present the idea to the whole group prior to them agreeing to their participation in the pilot project engagement. Only one engagement session was conducted with the Alianza group, on a Saturday for four continuous hours, as requested by the leaders. Co-planning the engagement with the Alianza group allowed EduCo to build a sense of partnership with them.

Planning Meeting:

- Describe project

- Establish goals

- Co-plan the engagement

Engagement:

- Cruise ship icebreaker

- World Café discussions

- Myths and realities

- Follow-up planning

Engagement Activities

All the engagement activities were conducted at facilities known and used by the participants. The engagement sessions were facilitated by EduCo staff, and other court professionals such as judges, attorneys, and court clerks. For some engagement sessions, representatives from partnering groups also played a role in facilitating activities. For example, an art teacher helped facilitate one of the group activities during the second Crearte school engagement.

Select Key Findings

Key findings drawn from the Puerto Rico engagements included:

- The Crearte youth group mentioned they did not have major conflicts in their alternative school but did see conflict in the greater community.

- The Boys and Girls Club youth felt that solving conflicts required honesty and maturity that had to be taught at home.

- The adults spoke about different examples of conflicts they observed in their communities such as noise, waste disposal, family conflict, and property demarcation between neighboring lands. Property rights seem to be intertwined with neighborhood conflicts.

- Community leaders mentioned the different techniques they use as leaders to help their neighbors resolve conflict but also mentioned that in some cases the issues had be taken to court.

Evaluation

Both youth and adult groups completed pre and post engagement surveys. Additionally, some court personnel who facilitated the engagement sessions completed surveys. Survey content included questions on prior experiences, perceptions, and knowledge of the court system; how the engagements equipped participants to address issues of community conflict; and satisfaction with the engagement experience. Across all four engagement sessions, 80 individuals completed surveys. Notable results included:

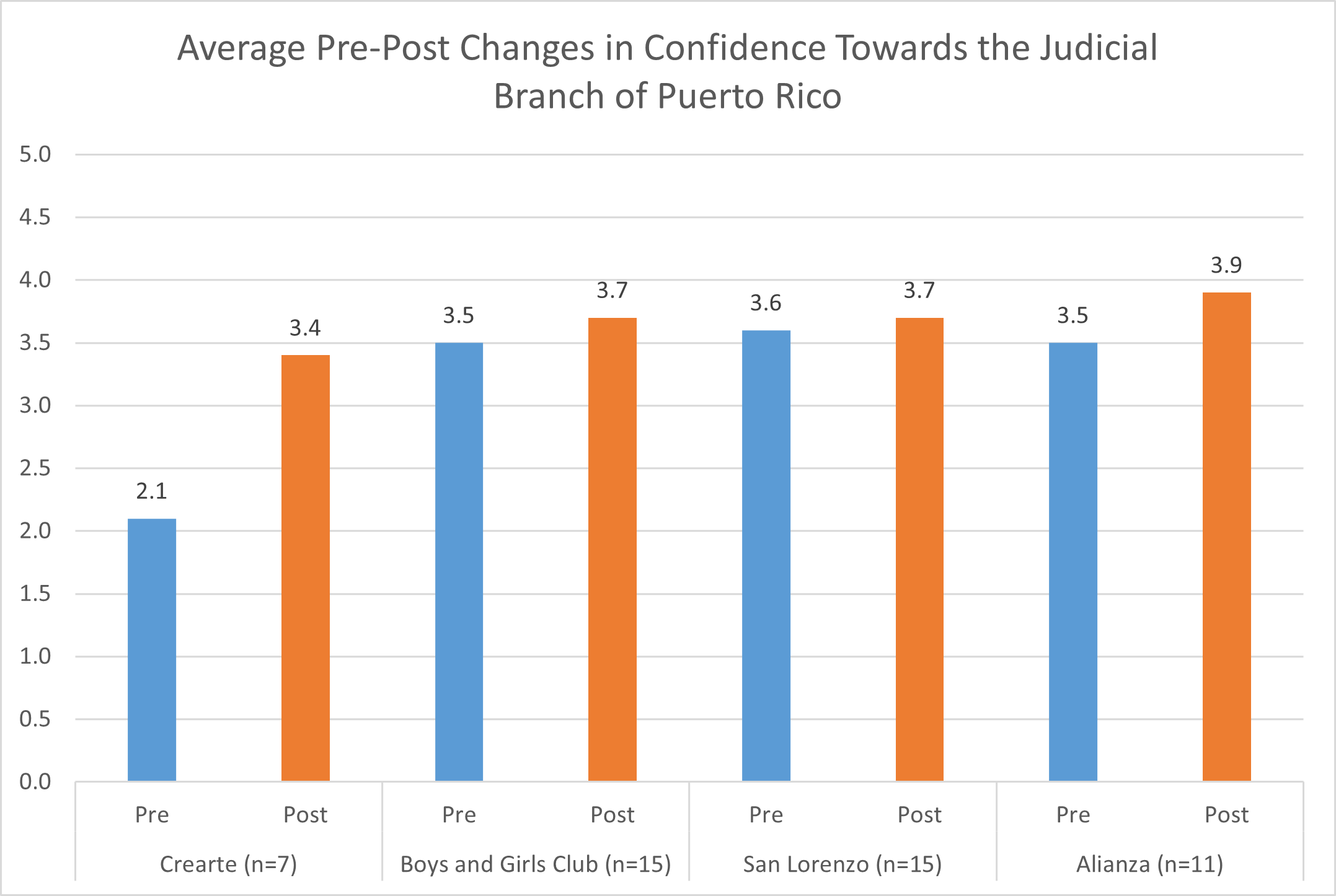

Before and after the community engagement, participants were asked to rate “I am confident in Puerto Rico's courts” on a scale of 1-5, where 1=“Strongly disagree” and 5=“Strongly agree.” The average score for confidence in Puerto Rico’s courts among all respondents increased after the engagement sessions.

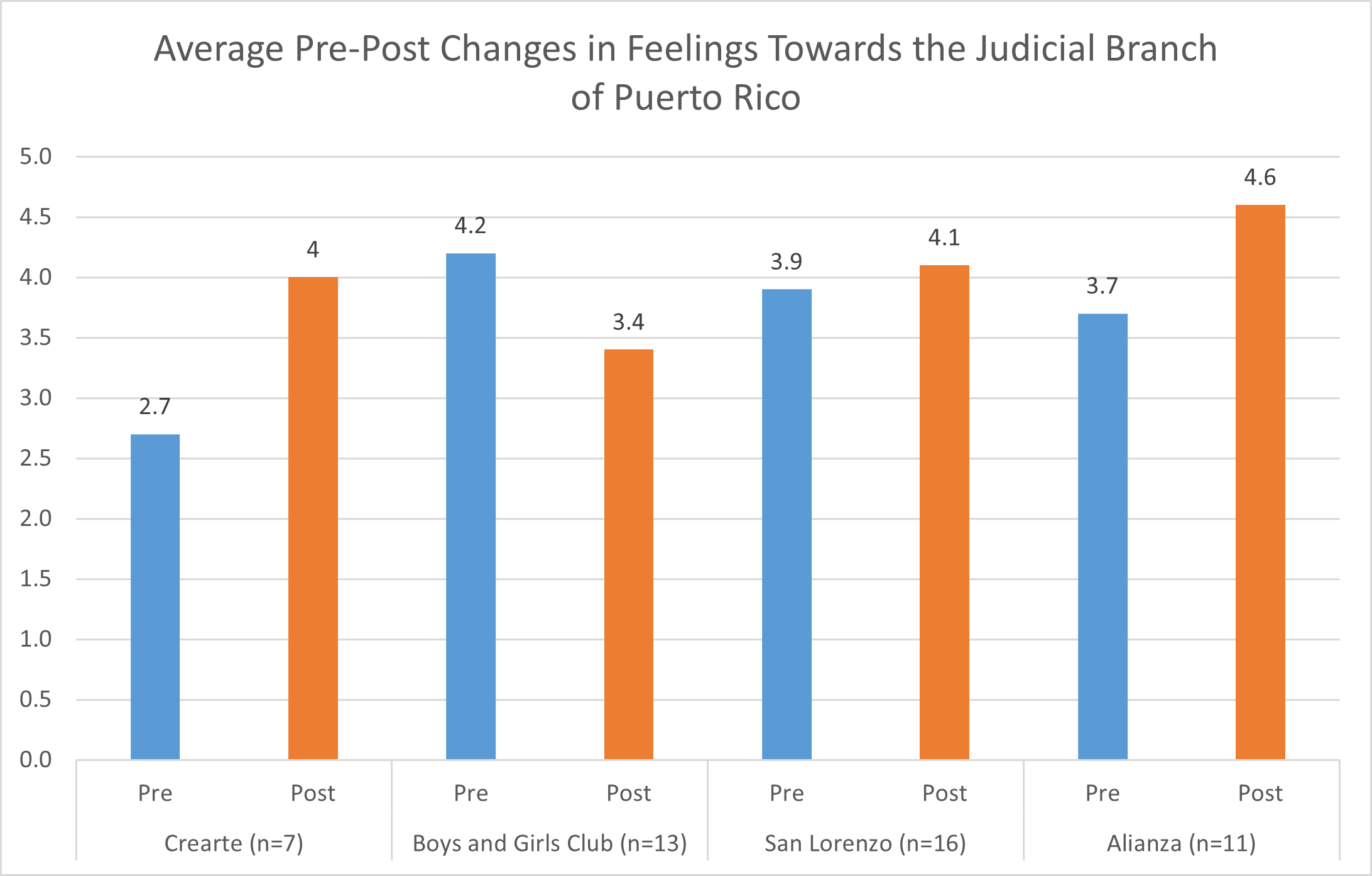

In addition, community engagement participants were asked: “In general terms, how would you describe your feelings towards the Judicial Branch of Puerto Rico?” Respondents answered on a scale of 1-5, where 1=“Completely negative” and 5=“Completely positive.” The average score for feelings towards the Judicial Branch of Puerto Rico among respondents generally increased. However, it is interesting that for the Boys and Girls Club chapter, it decreased when measured pre-post the first session (shown below). When measured again after the second session (not shown), it increased again, suggesting the value of multiple engagements.

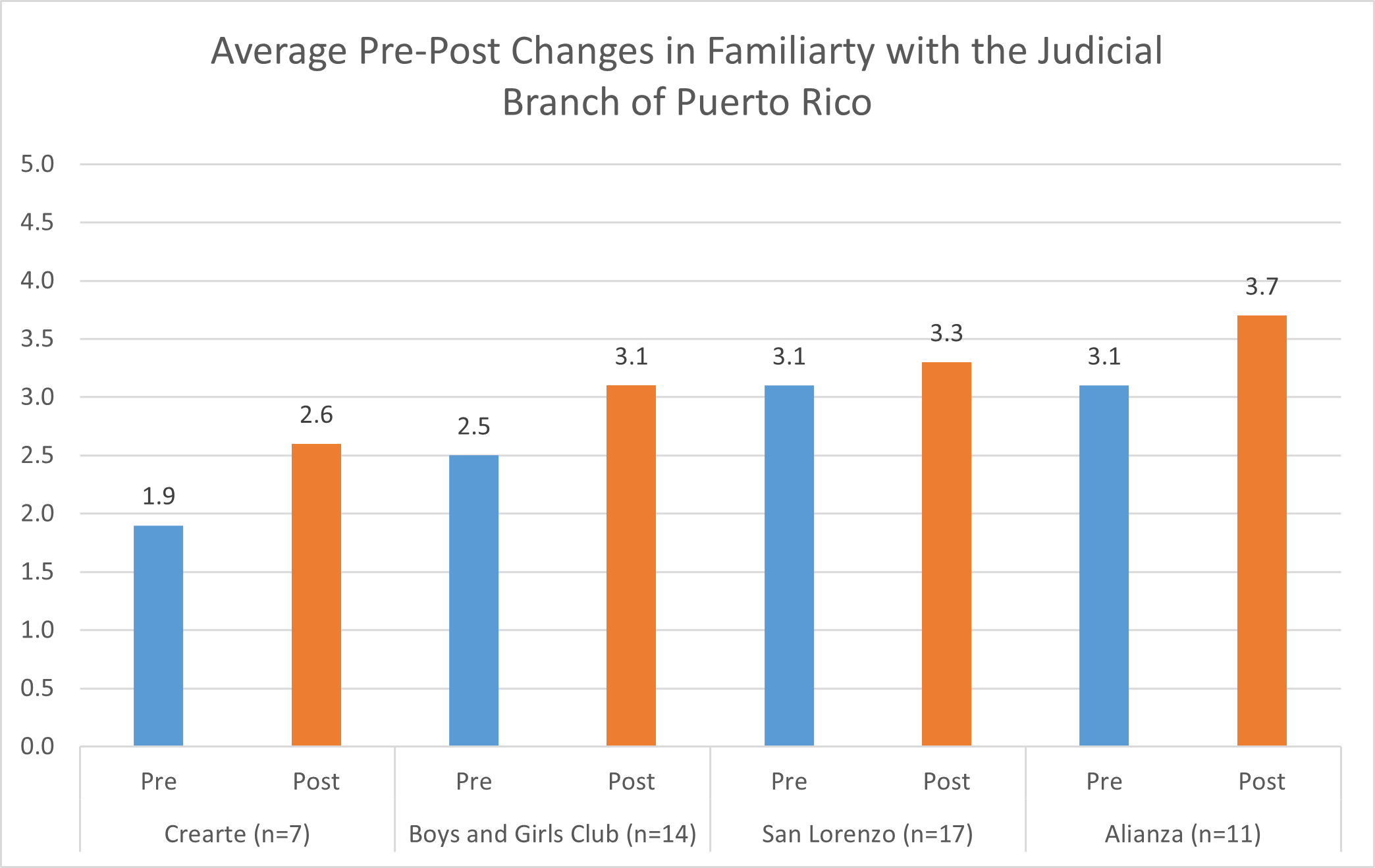

Although changes in objective knowledge of court professional roles and functions of the judicial branch did not appear to consistently increase, average reported familiarity with the judicial system in general increased after the engagements with all four community groups. Participants answered the question “How familiar are you with the Judicial Branch of Puerto Rico?” on a scale of 1-5 (1=“Not at all familiar”, 5=“Extremely familiar”).

The finding that one or two engagements is not enough to change prior objective knowledge and misconceptions about the judicial system supports the importance of using long-term strategies to engage and educate communities.

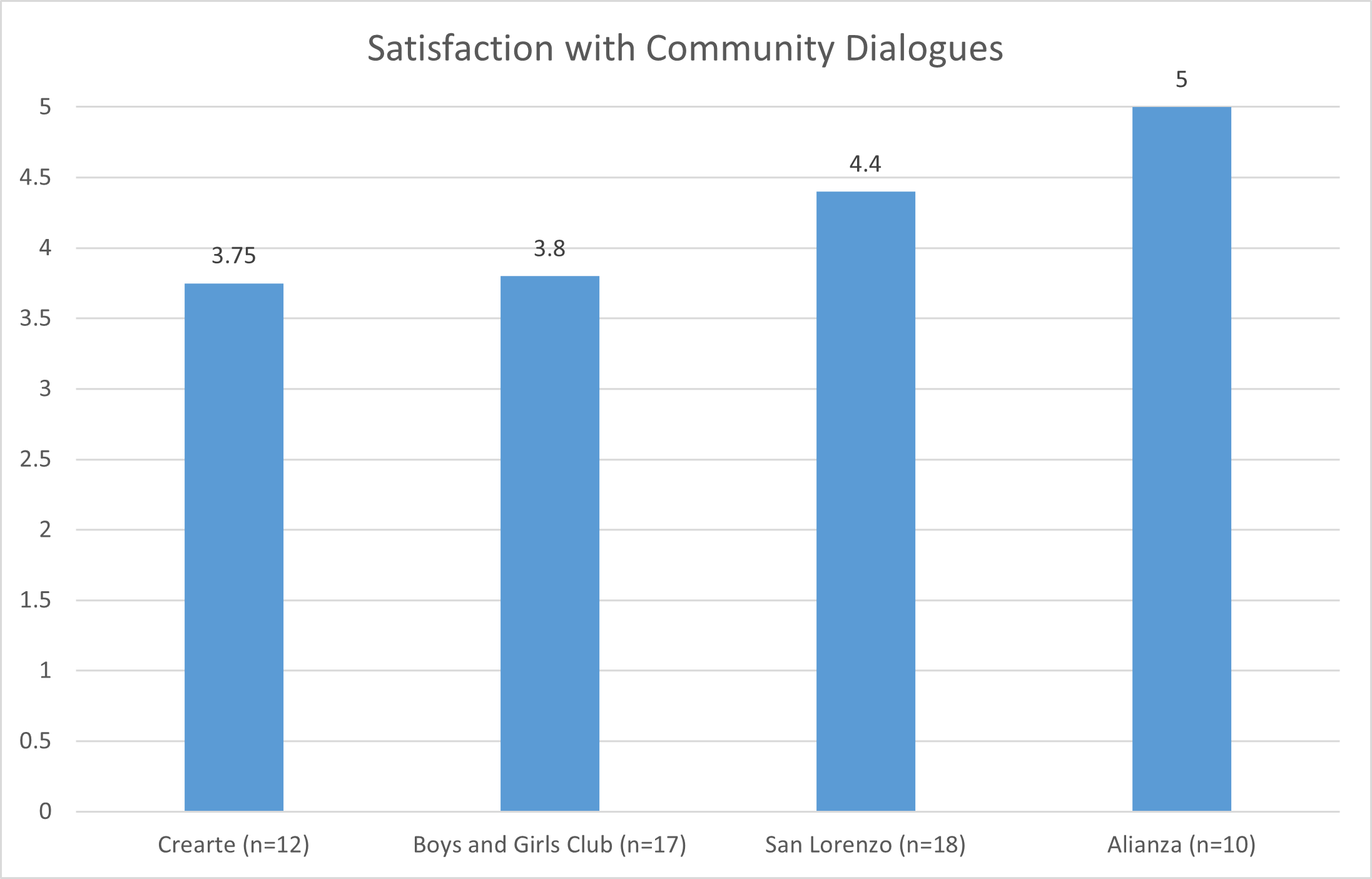

Among all four community groups, satisfaction with the engagement sessions was high. Participants were asked to rate to the item “I was satisfied with this community dialogue,” on a scale of 1-5, where 1 =“Strongly disagree”, 5=“Strongly agree.” The average satisfaction score for all engagement sessions fell between 3 (neutral) and 5 (strongly agree).

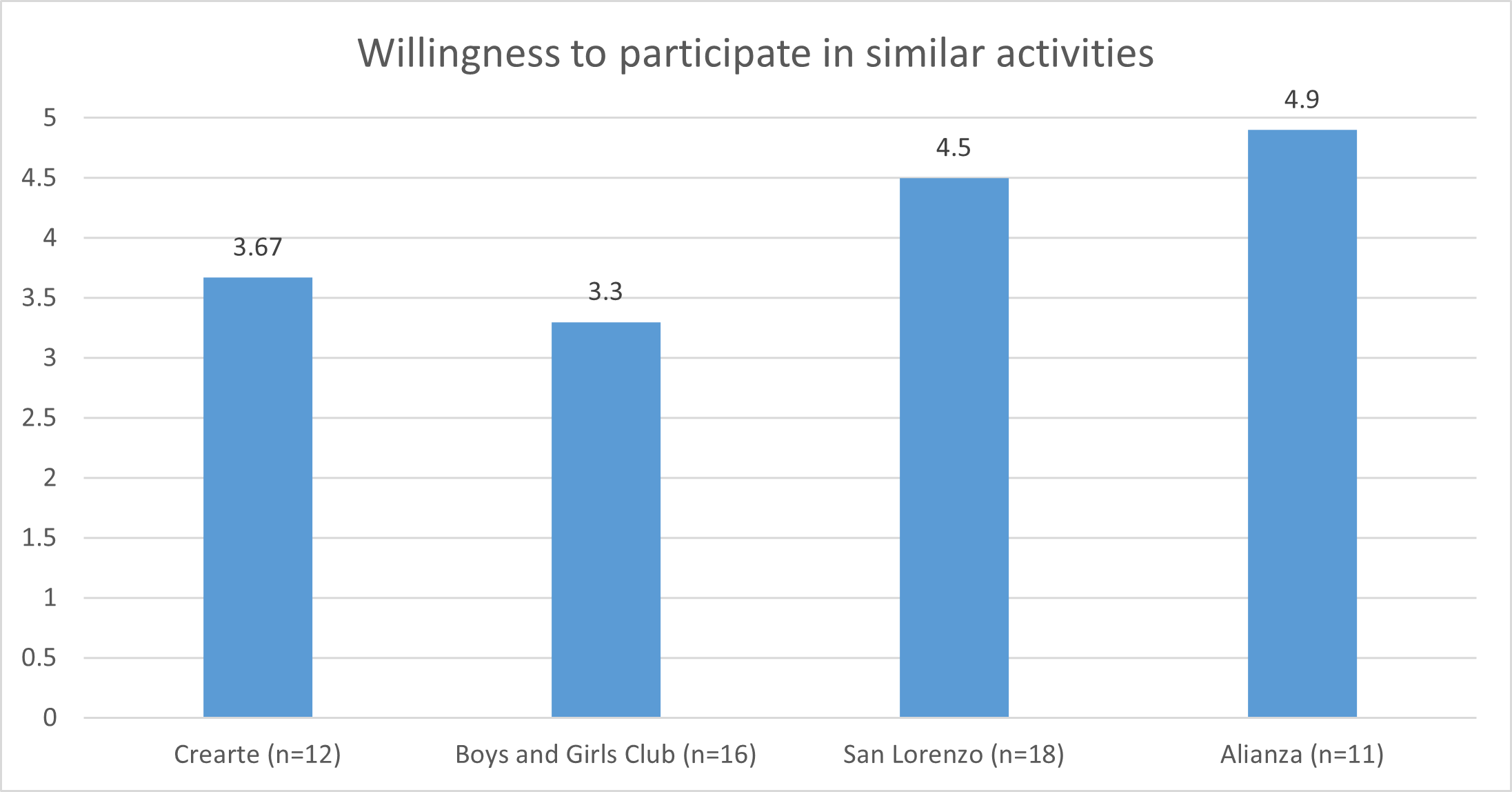

In addition, all four community groups expressed interest in participating in similar engagement activities in the future. On a scale of 1-5 (1 =“Strongly disagree”, 5 =“Strongly agree,” in response to the question “I would like to participate again in similar activities”), the answers fell between 3 (neutral) and 5 (strongly agree) for all engagement sessions.

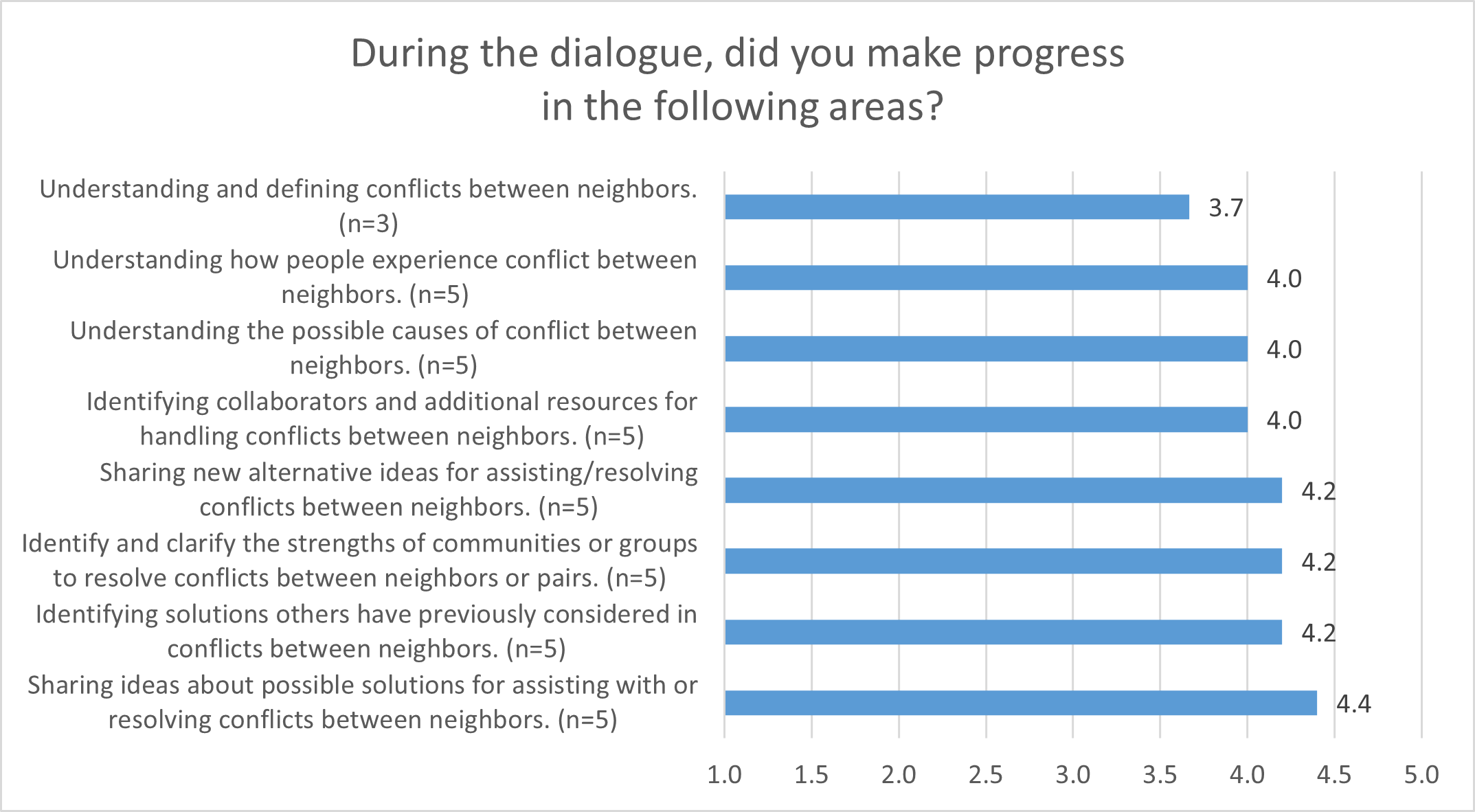

Court actors (judges, lawyers, and other court personnel) at the youth Puerto Rico engagements believed that the engagements resulted in positive progress regarding issues of community conflict. Average scores measuring perceptions of progress ranged from 3.7 to 4.4, on a scale of 1-5 (1=“Strongly disagree”, 5=“Strongly agree,” in response to the question “During the dialogue, did you make progress in the following areas?”).

Sustainability

The Puerto Rico team maintained relationships with its community engagement participants after the initial engagements were completed. EduCo worked with the four community groups to develop small scale follow-up activities to further build their relationships and generate further awareness about the Puerto Rico judiciary’s roles and functions.

Follow-up activities included:

The Puerto Rico pilot team and San Lorenzo community leaders have created three working groups to develop educational materials about judicial services available to the community to help resolve conflict. Each working group is composed of one judge, one lawyer, and three community representatives.

The Puerto Rico pilot project team is continuing to work with the Boys and Girls Club chapter of Carolina. The club members developed a script to produce a video about bullying. The script was then discussed with court personnel. In the future, the script could be used to create a video which then might provide a tool to further engage other youth groups as peer mentors and leaders.

Following the four engagement sessions, the Puerto Rico team surveyed 12 of the judges, lawyers, and other court personnel who participated in the engagement activities about their perceptions of the project. All (100%) of the respondents believed that conducting community engagements is very important for the judicial branch to better understand the community, and vice versa. Thus, these court personnel have continued to participate in other EduCo community initiatives and educational activities and have excelled as court personnel educational guides in Puerto Rico’s different judicial regions.

Lessons Learned

- Ensure stable and consistent leadership: The Puerto Rico judiciary benefited from having EduCo administer and lead the engagement project. An office like EduCo - which has personnel dedicated to community engagement and education - was critical for successfully administering the engagement project.

- Working with smaller community groups: Engaging community groups with smaller numbers through already existing community stakeholder connections had distinct advantages. Working with smaller community groups allowed EduCo to invest more time on attaining their engagement goals, rather than spending time managing logistics for larger events.

- Assess community knowledge of the court system: Opportunities to engage closely with community members and their understandings of the judicial system reinforced awareness of the need to make court services more accessible. Members of the EduCo leadership team and affiliated court actors identified the need to use simple and accessible language and approaches in future educational efforts.

- Avoid using multi-part engagement sessions: Three of the four engagement sessions were broken into two, two-hour meetings, due to scheduling constraints of the community groups. One engagement was a single, 4-hour meeting. EduCo and its partners found the single meeting was more cohesive and efficient than the two-part sessions. Working closely with stakeholder partners, especially youth groups who may have conflicting obligations such as school schedules, is an important logistical consideration to maximize productivity of engagement activities.

[1] Mission and Functions of the Press Office and the Office of Education and Community Relations, as reorganized under Administrative Order OAJ-2014-027, Circular Letter No. 8, Fiscal Year 2014-2015.