AI-generated evidence is a threat to public trust in the courts

By Connor Heaton (CivAI), Shay Cleary, and Michael Navin

When California Judge Victoria Kolakowski reviewed a video of a witness in Mendones v. Cushman & Wakefield, something felt wrong. The witness's face was nearly motionless, and the footage had strange cuts and apparent repetition of her mannerisms. The judge identified the evidence as AI-generated audio and video of a real person. The self-represented plaintiffs had submitted deepfake videos as authentic testimony.

The case appears to be one of the first instances where a deepfake was submitted as purportedly authentic evidence and detected as AI-generated. Judges have expressed concerns about fabricated and doctored documents submitted into evidence. Fabricated evidence is not a new problem for courts, but the technology to produce it has never been so accessible or inexpensive as it is now, especially for photos, audio, and video.

By the standards of today's AI capabilities, the video from Mendones is incredibly primitive. Today, anyone with an inexpensive monthly subscription to one of several common AI services can produce a higher-fidelity fake in moments.

Modern AI tools enable far more plausible versions of the Mendones fakes

Deepfake filed as evidence in Mendones vs. Cushman & Wakefield. Note the deepfake has very little resemblance to the actual witness.

Recreated deepfake produced by CivAI as an illustration using a popular consumer AI model. The new deepfake produced for this article was based on the court deepfake rather than the witness's actual likeness.

The threats posed by these AI tools are not limited to sophisticated video manipulation. In Florida, a woman spent two days in jail after her ex-boyfriend allegedly fabricated AI-generated text messages that led to her arrest for violating a protective order. "No one verified the evidence," she said. Prosecutors eventually dropped the charges, but only after eight months of legal proceedings.

AI can also produce fake documents & screenshots

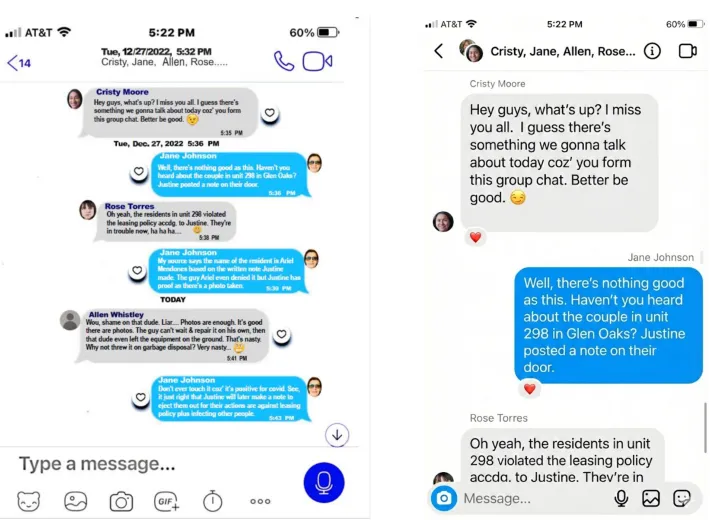

Left: Fake group message from Mendones evidence.

Right: Recreated fake group message produced by CivAI as an illustration, using a popular consumer AI model

Currently, AI-generated evidence is primarily an issue in cases where a party acts as their own legal representation, as in Mendones. Self-represented litigants also cite nonexistent cases, statutes, or quotations generated by AI tools far more frequently than lawyers do, with over 350 documented cases of this in the US.

That being said, legal professionals are not entirely exempt, accounting for more than 200 instances of false citations and quotations generated by AI. To date, there are no confirmed cases of lawyers knowingly submitting AI-generated evidence, but they are far from a perfect bulwark against dubious AI-generated content entering the courtroom. Mistakes in handling AI-generated content risk undermining public trust in the effectiveness of the legal system. A recent survey for the National Center for State Courts documents that the public is already concerned that AI will be harmful to the courts.

AI capabilities cast doubt on authentic evidence

The capability for AI to produce plausible fakes also makes it easier to discredit legitimate proof. Defense attorneys have begun invoking "the deepfake defense," a term that describes how the ease of producing deepfakes enables bad actors to dismiss true recordings as fabrications.

Some types of evidence — which previously would have been considered nearly ironclad — are now cast into doubt. Judge Erica Yew of California's Santa Clara County Superior Court recently raised a troubling scenario to NBC News: someone could generate a false vehicle title record and present it to a county clerk who, lacking the expertise to identify it as fraudulent, would enter it into official records. A litigant could then obtain a certified copy and present it as authentic documentation. "Now do I, as a judge, have to question a source of evidence that has traditionally been reliable?" Yew asked. "We're in a whole new frontier." This same risk applies to other filings which are handled administratively, selectively including aid eligibility, licenses, minor settlements, probate packets, and vital records.

Chief Judge Anna Blackburne-Rigsby of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals articulated the core concern in ABC News interview: "If you're in a trial court presenting a case and you're afraid as a litigant or as a party, maybe the other side is using evidence that's been altered by artificial intelligence — does the judge know? Does the judge understand how this could impact my case?" The issue, she said, cuts to whether people believe the legal process is fair.

Courts are responding

This rise in fabricated evidence comes at a time when defensive technologies are still unable to reliably identify AI-generated content, especially when even basic post-processing like filtering has been applied. Detection tools are at a disadvantage in the arms race against ever more realistic AI systems. Detection tends to be brittle, showing high accuracy on clean datasets but collapsing when faced with real-world fakes, and often needs to be recalibrated when new AI tools are released.

Judges are already managing heavy caseloads. If every disputed voicemail, video, or screenshot required a forensic investigation, the system could slow to a crawl, and parties who lack the resources to hire experts could be disadvantaged. Dismissals send a powerful message, but courts also need an efficient way to address deepfakes.

Fortunately, courts and policymakers have begun to respond. Proposed Rule of Evidence 707 would subject machine-generated evidence to the same reliability standards as expert testimony. The AI Task Force of California's Judicial Council is developing guidance for evaluating AI-generated evidence. The National Center for State Courts has published bench cards to help judges assess both acknowledged and unacknowledged AI-generated materials.

These efforts are important steps in the right direction. AI tools can offer genuine benefits to courts, including streamlining case management and assisting self-represented litigants in navigating complex procedures. However, realizing those benefits requires maintaining the integrity of evidence that underpins trust in the courts.

The judicial system's de facto legitimacy rests on public confidence that disputes will be resolved based on facts. If litigants believe fabricated evidence can prevail — or that legitimate proof will be wrongly dismissed as AI-generated — that confidence erodes. The deepfake in Mendones was caught because it used obsolete technology. Future fakes will not be so obvious.

This article was developed by NCSC and CivAI as part of a collaborative effort to educate court leaders on AI‑related risks, including emerging cybersecurity threats.

Explore more

AI-generated evidence: A guide for judges

Helping judges evaluate AI-generated content and ensure fair, informed decisions that preserve the integrity of judicial proceedings.

Evaluating unacknowledged AI-generated evidence

Guidance on issues raised by unacknowledged AI-generated evidence and suggested questions or areas of inquiry for the court to help inform a determination about the authenticity of digital evidence alleged to be unacknowledged AI-generated evidence.

Evaluating acknowledged AI-generated evidence

Guidance on questions or areas of inquiry a trial court may consider using to help inform a determination whether to admit acknowledged AI-generated evidence.